February 2025

Achieving better techniques for DNA preservation and recovery

Natural History Museums around the world hold vast collections of plants and animals, seized, catalogued, preserved and stored in an attempt to capture a snapshot of their living bodies, a glimpse of their biological nature forever fixed in time. Back when the first naturalists started venturing into unexplored regions in search of plants and animals still unknown to science, it became apparent that the work for catching and properly preserving flora and fauna in the field posed huge challenges. None other than Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913) quite accurately described the intricacies of specimen collection and preparation during one of his numerous travels and dangerous adventures:

[on the difficulties of preserving bird skins] “The lean and hungry dogs before mentioned were my greatest enemies, and kept me constantly on the watch. If my boys left the bird they were skinning for an instant, it was sure to be carried off. Everything eatable had to be hung up to the roof, to be out of their reach. Ali had just finished skinning a fine King Bird of Paradise one day, when he dropped the skin. Before he could stoop to pick it up, one of this famished race had seized upon it, and he only succeeded in rescuing it from its fangs after it was torn to tatters. Two skins of the large Paradisea, which were quite dry and ready to pack away, were incautiously left on my table for the night, wrapped up in paper. The next morning they were gone, and only a few scattered feathers indicated their fate.” (From Wallace’s 1869 book The Malay Archipelago) [1].

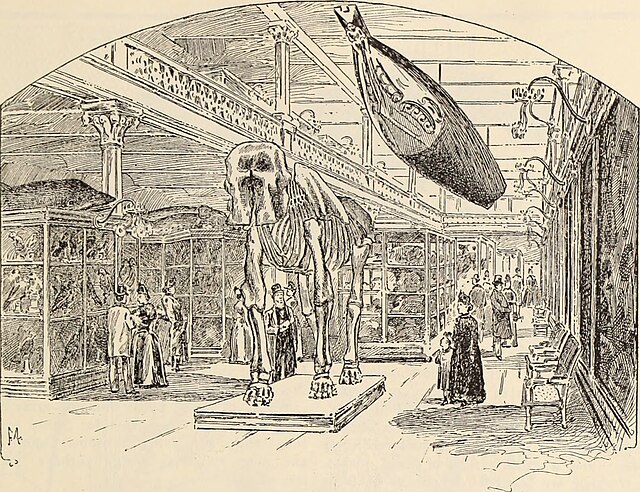

The American Museum of Natural History" in Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, Vol. XXXI, No. 4 (page 393). 1981.

These pioneers had no knowledge of molecular biology, yet they were similarly preoccupied with obtaining the best preservation possible of once-living specimens to be stored in museum collections for their study. Beyond external and morphological fixation of skins and other tissues to permanently capture the looks of living species, now dead and stored far away from their habitats, the advent of DNA recovery and sequencing from ancient and historical specimens opened a new range of previously unrecognized challenges. More than a mere aesthetic fixation, it became painfully evident that most of the chemicals and procedures undergone a long time ago on many museum specimens might not have been the best to ensure proper DNA survival within the tissues.

Mirroring the many challenges endured by early naturalists, Dr. Alexander Salis has embarked on a highly relevant endeavor: To elucidate the best ways to extract and isolate DNA from ancient and historical specimens, and to describe the best practices needed for preserving DNA from freshly collected specimens. His research focused on investigating the possible source of known DNA degradation observed in flash-frozen archival tissues from different organisms [2]. He first analyzed samples in which liquid nitrogen-based frozen storage had failed to remain stable and uninterrupted. In these, he found quite a significant amount of DNA degradation, making it almost undetectable or remarkably degraded. Those samples were considered a natural worst-case scenario of poor DNA preservation in archived tissues. He then analyzed how DNA would be preserved in samples first fixed with ethanol or dedicated buffers, compared to tissues where just flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen was performed. Both ethanol and fixative buffers outperformed flash-freezing in terms of DNA fragment size and integrity, but overall DNA yield was reduced. Nevertheless, an elevated variability in the amount of DNA isolated was a common finding for all methods applied. In their work [2], they hypothesize that the origin of such a DNA degradation found for flash-frozen tissues might be due to successive freeze-thaw events occurred through time as researchers attempted to work on the samples for DNA isolation. Ethanol or fixative buffers would have protected the DNA from degradation upon thawing for laboratory working, while simply flash-frozen tissues would have suffered different rates of DNA damage and degradation each time they were thawed and processed.

As a continuation of his first insights, Dr. Salis is now expanding the optimization of DNA preservation and recovery to wet collections in museums, working with archival samples fixed with ethanol or formalin solutions, in an attempt to increase the success rate and quality of nucleic acids extracted from these tissues, which are particularly known to be tricky and hard to process. We will certainly keep an eye on his work so that researchers dealing with wet collections and cryopreserved tissues over long periods of time might find new approaches and go-to recommendations to ensure the best possible results when obtaining nucleic acids for museomics applications.

References

- Wallace, A. R. The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orangutan, and the Bird of Paradise (Macmillan, 1869).

- Salis, A. T. et al. Unrecognised DNA degradation in flash-frozen genetic samples in Natural History Collections. Mol Ecol Resour e14121 (2025).

Below, Alexander shared with us further details about his profile, career, prospects and future projects:

1. Briefly introduce yourself. What is your origin story for how you got into science?

Growing up in Dunedin, a small city on the South Island of New Zealand, I was surrounded by nature — seabirds such as albatrosses, shags, and cormorants, along with penguins and marine mammals like fur seals and sea lions. This early exposure instilled in me a deep curiosity and appreciation about animals and the natural world. While studying at the University of Otago, I had the opportunity to use ancient DNA to investigate how human settlement may have impacted fur seals. Eager to explore such concepts further, I pursued a PhD at the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA supervised by Dr. Kieren Mitchell, where I focused on investigating how past environmental changes impacted the evolutionary history of carnivorans.

2. How and/or why did you start working on this project?

This project formed the core of my postdoctoral fellowship at the American Museum of Natural History. What drew me to this fellowship was the opportunity to apply my expertise in ancient DNA to museum specimens, with the goal of better integrating natural history collections into genetic research.

3. Were there any major challenges in this project? How did you overcome them?

Formalin fixation has long been a major obstacle to incorporating natural history collections into genetic research. A key focus of this project was to develop and test extraction protocols specifically for formalin-fixed specimens. Our results, along with our soon to be published protocol, will hopefully provide a valuable contribution to the field and help others overcome this major hurdle.

4. What do you think are the main take-home messages of this project?

5. What do you think is missing in the field that you would like to work on?

There is still considerable room to expand our understanding of how different museum fixatives and preservatives (e.g., formalin, ethanol, arsenic, etc.) degrade DNA and how this degradation impacts sequencing outcomes and downstream bioinformatic analyses.

6. Where do you see yourself in the near future?

I hope to secure a research position that allows me to continue working with ancient and historical DNA, with a particular focus on improving the integration of challenging or suboptimal DNA sources into genomic research.